Over a career spanning almost four decades, I spent more than 27 years in international agricultural research in South and Central America, and Asia. And a decade teaching at the University of Birmingham.

It all started on this day, 50 years ago, when I joined the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru as an Associate Taxonomist.

It all started on this day, 50 years ago, when I joined the International Potato Center (CIP) in Lima, Peru as an Associate Taxonomist.

But first, let me take you back a couple of years, to September 1970.

I’d enrolled at the University of Birmingham for the MSc degree in Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources, taught in the Department of Botany. It was the following February that I first heard about the possibility of joining CIP.

The head of department, potato expert Professor Jack Hawkes had just returned from a six week expedition to Bolivia (to collect wild species of potato) that was supported, in part, by the USAID-North Carolina State University-sponsored potato program in Peru.

The American joint leader of that program, Dr Richard Sawyer (left), mentioned to Jack that he wanted to send a young Peruvian scientist, Zosimo Huamán, to Birmingham for the MSc course in September 1971, and could he suggest anyone to fill a one-year vacancy.

The American joint leader of that program, Dr Richard Sawyer (left), mentioned to Jack that he wanted to send a young Peruvian scientist, Zosimo Huamán, to Birmingham for the MSc course in September 1971, and could he suggest anyone to fill a one-year vacancy.

On the night of his return to Birmingham, Jack phoned me about this exciting opportunity. And would I be interested. Interested? I’d long had an ambition to travel to South America, and Peru in particular.

However, my appointment at CIP was delayed until January 1973. Why? Let me explain.

In 1971, Sawyer was in the final stages of setting up the International Potato Center. However, a guaranteed funding stream for this proposed research center had not been fully identified.

At that time, there were four international agricultural research centers:

- the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in Los Baños, the Philippines (founded in 1960);

- the International Center for the Improvement of Maize and Wheat (CIMMYT) near Mexico City (1966);

- the International Institute for Tropical Agriculture (IITA) in Ibadan, Nigeria (1967); and

- the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in Cali, Colombia (also 1967).

All received bilateral funding from several donors, like the non-profit Rockefeller and Ford Foundations for example, or government agencies like USAID in the USA or the UK’s Overseas Development Administration.

In May 1971 there was a significant development in terms of long-term funding for agricultural research with the setting up of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research or CGIAR (an umbrella organization of donors, run from the World Bank in Washington, DC) to coordinate and support the four centers I already mentioned, and potentially others (like CIP) that were being established.

In May 1971 there was a significant development in terms of long-term funding for agricultural research with the setting up of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research or CGIAR (an umbrella organization of donors, run from the World Bank in Washington, DC) to coordinate and support the four centers I already mentioned, and potentially others (like CIP) that were being established.

Since its inception, CGIAR-supported research was dedicated to reducing rural poverty, increasing food security, improving human health and nutrition, and ensuring more sustainable management of natural resources.

For more than 50 years, CGIAR and partners have delivered critical science and innovation to feed the world and end inequality. Its original mission—to solve hunger—is now expanding to address wider 21st century challenges, with the aim of transforming the world’s food, land, and water systems in a climate crisis. More on that below.

Back in 1971 the question was which funding agencies would become CGIAR members, and whether CIP would join the CGIAR (which it did in 1973).

Throughout 1971, Sawyer negotiated with the UK’s ODA to support CIP. But with the pending establishment of the CGIAR, ODA officials were uncertain whether to join that multilateral funding initiative or continue with the current bilateral funding model.

Decisions were, in the main, delayed. But one important decision did affect me directly. The ODA gave me a personal grant in September 1971 to remain in Birmingham until funding to CIP could be resolved. I therefore registered for a PhD on potatoes under Jack Hawkes’ supervision, and spent the next 15 months working on ideas I hoped to pursue further once I could get my hands on potatoes in the Andes, so to speak.

With Jack Hawkes in the potato field genebank at Huancayo, central Peru (3100 m above sea level) in early 1974.

In the event, the ODA provided £130,000 directly to CIP between 1973 and 1975 (= £1.858 million today), which funded, among other things, development of the center’s potato genebank, germplasm collecting missions around Peru, and associated research, as well as my position at the center.

Arriving in Peru was an ambition fulfilled, and working at a young center like CIP was a dream come true, even though, at just 24, I was somewhat wet behind the ears.

However, there were some great colleagues who taught me the ropes, and were important mentors then and throughout my career. I learnt a lot about working in a team, and about people management, very useful in later years as I moved up the management ladder.

For the first three years, my work was supervised and generously supported by an American geneticist, Dr Roger Rowe (right, with his wife Norma) who joined CIP on 1 May 1973 as head of the Breeding and Genetics Department. I owe a great deal to Roger who has remained a good friend all these years.

For the first three years, my work was supervised and generously supported by an American geneticist, Dr Roger Rowe (right, with his wife Norma) who joined CIP on 1 May 1973 as head of the Breeding and Genetics Department. I owe a great deal to Roger who has remained a good friend all these years.

Always leading from the front, and never shy of making the tough decisions, Roger went on to fill senior management positions at several CGIAR centers. As a former colleague once commented to me, “Roger was the best Director General the CGIAR never had.” I couldn’t agree more.

When I joined CIP’s Regional Research group in 1976 and moved to Costa Rica, my new boss was Ken Brown (left). Ken had been working as a cotton physiologist in Pakistan for the Cotton Research Corporation, although he had previously worked in several African countries.

When I joined CIP’s Regional Research group in 1976 and moved to Costa Rica, my new boss was Ken Brown (left). Ken had been working as a cotton physiologist in Pakistan for the Cotton Research Corporation, although he had previously worked in several African countries.

Ken never micromanaged his staff, was always there to help set priorities and give guidance. In those aspects of people management, I learned a lot from Ken, and he certainly earned my gratitude.

Aside from my work on potato genetic resources (and completing my PhD in 1975), I enjoyed the work on bacterial wilt and setting up a regional program, PRECODEPA as part of my Regional Research activities.

Jim Bryan (right, with Costarrican assistant Jorge Aguilar) was my closest friend at CIP. A native of Idaho, Jim was CIP’s seed production specialist. Down to earth and pragmatic, Jim taught me the importance of clean potato seed and seed production systems. He came to work with me in Costa Rica during 1979/80 and together we worked on a successful project (with the Costarrican Ministry of Agriculture) for the rapid multiplication of seed potatoes.

Jim Bryan (right, with Costarrican assistant Jorge Aguilar) was my closest friend at CIP. A native of Idaho, Jim was CIP’s seed production specialist. Down to earth and pragmatic, Jim taught me the importance of clean potato seed and seed production systems. He came to work with me in Costa Rica during 1979/80 and together we worked on a successful project (with the Costarrican Ministry of Agriculture) for the rapid multiplication of seed potatoes.

But by the end of 1980, I was looking for a new challenge when one came to my attention back home in the UK.

In April 1981, I joined the University of Birmingham as a Lecturer in the Department of Plant Biology (as the Department of Botany had been renamed since I graduated).

In April 1981, I joined the University of Birmingham as a Lecturer in the Department of Plant Biology (as the Department of Botany had been renamed since I graduated).

I have mixed feelings about that decade. Enthusiastic for the first few years, I became increasingly disenchanted with academic life. I enjoyed teaching genetic resources conservation to MSc students from many different countries, and particularly supervision of graduate students. I also kept a research link on true potato seed (TPS) with CIP, and around 1988 participated in a three-week review of a Swiss-funded seed production project at four locations in Peru.

With members of the project review team, with team leader Carlos Valverde on the right. Cesar Vittorelli, our CIP liaison is in the middle. I don’t remember the names of the two other team members, a Peruvian agronomist, on my right, and a Swiss economist between Vittorelli and Valverde.

But universities were under pressure from the Tory government of Margaret Thatcher. It was becoming a numbers, performance-driven game. And even though the prospects of promotion to Senior Lecturer were promising (I was already on the SL pay scale), by 1991 I was ready for a change.

And so I successfully applied for the position of Head of the Genetic Resources Center at IRRI, and once again working under the CGIAR umbrella. I moved to the Philippines in July, and stayed there for the next 19 years until retiring at the end of April 2010.

And so I successfully applied for the position of Head of the Genetic Resources Center at IRRI, and once again working under the CGIAR umbrella. I moved to the Philippines in July, and stayed there for the next 19 years until retiring at the end of April 2010.

I was much happier at IRRI than Birmingham, although there were a number of challenges to face: both professional and personal such as raising two daughters in the Philippines (they were 13 and 9 when we moved to IRRI) and schooling at the International School Manila.

Whereas I’d joined CIP at the beginning of its institutional journey in 1973, IRRI already had a 30 year history in 1991. It was beginning to show its age, and much of the infrastructure built in the early 1960s had not fared well in the tropical climate of Los Baños and was in dire need of refurbishment.

A new Director General, Dr Klaus Lampe (right) from Germany was appointed in 1988 with a mandate to rejuvenate the institute before it slipped into terminal decline. That meant ‘asking’ many long-term staff to move on and make way for a cohort of new and younger staff. I was part of that recruitment drive. But turning around an institute with entrenched perspectives was no mean feat.

A new Director General, Dr Klaus Lampe (right) from Germany was appointed in 1988 with a mandate to rejuvenate the institute before it slipped into terminal decline. That meant ‘asking’ many long-term staff to move on and make way for a cohort of new and younger staff. I was part of that recruitment drive. But turning around an institute with entrenched perspectives was no mean feat.

With responsibility for the world’s largest and most important rice genebank, and interacting with genebank colleagues at all the other centers, I took on the chair of the Inter-Center Working Group when we met in Ethiopia in January 1993, and in subsequent years took a major role in setting up the System-wide Genetic Resources Program (SGRP). This was a forerunner—and a successful one at that—of the programmatic approach adopted by the CGIAR centers.

With responsibility for the world’s largest and most important rice genebank, and interacting with genebank colleagues at all the other centers, I took on the chair of the Inter-Center Working Group when we met in Ethiopia in January 1993, and in subsequent years took a major role in setting up the System-wide Genetic Resources Program (SGRP). This was a forerunner—and a successful one at that—of the programmatic approach adopted by the CGIAR centers.

The Swiss-funded project to collect and conserve rice varieties from >20 countries, and the innovative and pioneer research about on-farm conservation were highlights of the 1990s. As was the research, in collaboration with my old colleagues at Birmingham, on the use of molecular markers to study and conserve germplasm. A first for the CGIAR centers. Indeed a first for any crop.

The Swiss-funded project to collect and conserve rice varieties from >20 countries, and the innovative and pioneer research about on-farm conservation were highlights of the 1990s. As was the research, in collaboration with my old colleagues at Birmingham, on the use of molecular markers to study and conserve germplasm. A first for the CGIAR centers. Indeed a first for any crop.

Helping my genebank staff grow in their positions, and seeing them promoted gave me great satisfaction. I’d inherited a staff that essentially did what they were told to do. With encouragement from me they took on greater responsibility—and accountability—for various genebank operations, and their enthusiastic involvement allowed me to make the necessary changes to how the genebank was managed, and putting it at the forefront of CGIAR genebanks, a position it retains today.

My closest friend and colleague at IRRI was fellow Brit and crop modeller, Dr John Sheehy (right). John joined the institute in 1995, and I was chair of his appointment committee. Within a short time of meeting John for the first time, I recognized someone with a keen intellect, who was not constrained by a long-term rice perspective, and who would, I believed, bring some exceptional scientific skills and thinking to the institute.

My closest friend and colleague at IRRI was fellow Brit and crop modeller, Dr John Sheehy (right). John joined the institute in 1995, and I was chair of his appointment committee. Within a short time of meeting John for the first time, I recognized someone with a keen intellect, who was not constrained by a long-term rice perspective, and who would, I believed, bring some exceptional scientific skills and thinking to the institute.

Among his achievements were a concept for C4 rice, and persuading the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to back a worldwide consortium (now administered from the University of Oxford) of some of the best scientists working on photosynthesis to make this concept a reality.

By May 2001, however, change was in the air. I was asked to leave the Genetic Resources Center (and research) and join IRRI’s senior management team as Director for Program Planning and Communications, to reconnect the institute with its funding donors, and develop a strategy to increase financial support. I also took IT Services, the Library and Documentation Services, Communication and Publication Services, and the Development Office under my wing.

IRRI’s reputation with its donors was at rock bottom. Even the Director General, Ron Cantrell, wasn’t sure what IRRI’s financial and reporting commitments were.

We turned this around within six months, and quickly re-established IRRI as a reliable partner under the CGIAR. By the time I left IRRI in 2010, my office had helped the institute increase its budget to US$60 million p.a.

This increased emphasis on funding was important as, by the end of the 1990s, several donors were raising concerns about the focus of the centers and how they should be supported. Furthermore, a number of external factors like the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD, agreed by 150 countries in 1992), the growing consensus on the threat of climate change, the adoption of the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs, and subsequent Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs) meant that the 15 CGIAR centers as they had become could not continue with ‘business as usual’.

Until the end of the 1990s, each center had followed its own research agenda. But it became increasingly clear that they would have to cooperate better with each other and with the national programs. And funding was being directed at specific donor-led interests.

There is no doubt that investment in the CGIAR over 50 years has brought about great benefits, economically and in humanitarian ways. Investment in crop genetic improvement has been the mainstay of the CGIAR, and although research on natural resources management (NRM, such as soils and water) has been beneficial at local levels, it has not had the widespread impact that genetic improvement has.

The impact of the CGIAR is well-documented. Take this 2010 paper for example. Click on the image for more information.

My good friend from the University of Minnesota, Professor Phil Pardey and two colleagues have calculated the economic benefits of CGIAR to be worth about 10 times the cost. Impressive. Click on the image below for more information.

I have watched a couple of decades of CGIAR navel gazing as the system has tried to ‘discover’ the best modus operandi to support national programs and the billions of farmers and consumers who depend on its research outputs.

I have watched a couple of decades of CGIAR navel gazing as the system has tried to ‘discover’ the best modus operandi to support national programs and the billions of farmers and consumers who depend on its research outputs.

There’s no doubt these changes have increased bureaucracy across the CGIAR. One early development was the introduction of 3-year rolling Medium Term Plans with performance targets (always difficult in agricultural and biological research), which led to perverse incentives as many centers set unambitious targets that would attract high scores and therefore guarantee continued donor support.

I did not favor that approach (supported by my DG), encouraging my colleagues to be more ambitious and realistic in their planning. But it did result in conflict with an accountant in the World Bank – a ‘bean counter’ – who had been assigned to review how the centers met their targets each year. I don’t remember his name. We had endless arguments because, it seemed to me, he simply didn’t understand the nature of research and was only interested if a particular target had been met 100%. Much as I tried to explain that reaching 75% or perhaps lower could also mean significant impact at the user level, with positive outcomes, he would not accept this point of view. 100% or nothing! What a narrow perspective.

A former colleague in the CGIAR Independent Evaluation Arrangement office in Rome and a colleague have written an excellent evaluation of this performance management exercise, warts and all. Click on the image below to access a PDF copy.

Now we have OneCGIAR that is attempting to make the system function as a whole. Very laudable, and focusing on these five highly relevant research initiatives. Click on the image below for more information.

What I’m not sure about are the levels of management that the new structure entails: global directors, regional directors, program or initiative leaders, center directors (some taking on more than one role). Who reports to whom? It seems overly complicated to my simple mind. And there is certainly less emphasis on the centers themselves – despite these being the beating heart of the system. It’s not bureaucrats (for all their fancy slogans and the like) who bring about impacts. It’s the hard-working scientists and support staff in the centers.

Nevertheless, looking back on 50 years, I feel privileged to have worked in the CGIAR. I didn’t breed a variety of rice, wheat, or potatoes that were grown over millions of hectares. I didn’t help solve a water crisis in agriculture. But I did make sure that the genetic resources of potato and rice that underpin future developments in those crops were safe, and ready to be used by breeders whenever. I also helped IRRI get back on its feet, so to speak, and to survive.

And along the way, I did make some interesting contributions to science, some of which are still being cited more than four decades later.

I’m more than grateful for the many opportunities I’ve been afforded.

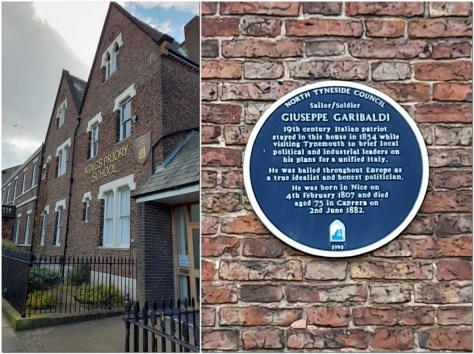

Built in 1872, there have been numerous famous visitors, among them comedy duo

Built in 1872, there have been numerous famous visitors, among them comedy duo

Well, in early 2011 I came across a book in the public library in Bromsgrove (in Worcestershire where I used to live) about US army officer, Indian fighter, explorer and adventurer, Colonel Christopher Houston ‘Kit’ Carson (1809-1868). Kit Carson was a western ‘hero’ of my boyhood, a figure in popular western culture and myth.

Well, in early 2011 I came across a book in the public library in Bromsgrove (in Worcestershire where I used to live) about US army officer, Indian fighter, explorer and adventurer, Colonel Christopher Houston ‘Kit’ Carson (1809-1868). Kit Carson was a western ‘hero’ of my boyhood, a figure in popular western culture and myth.

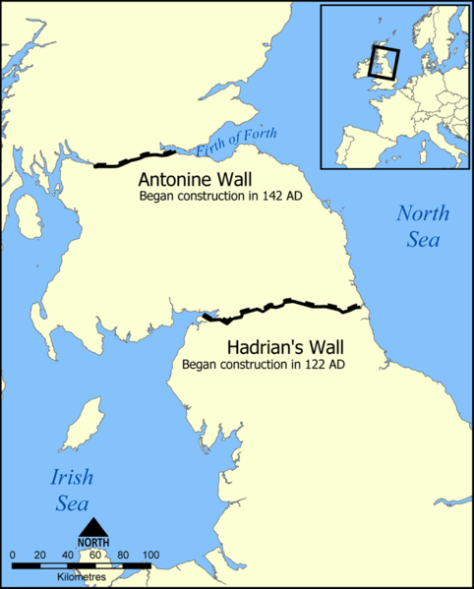

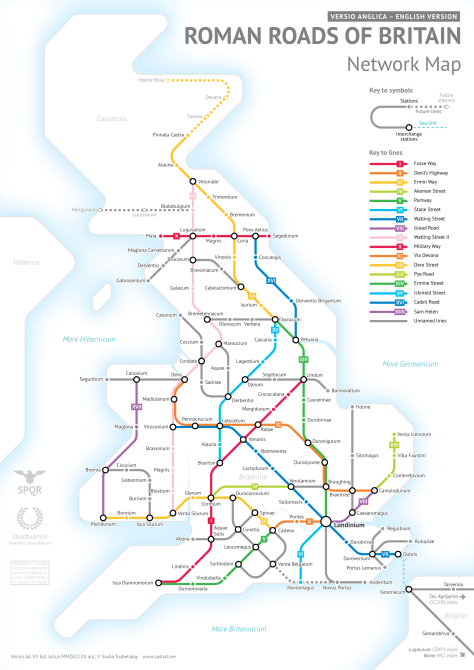

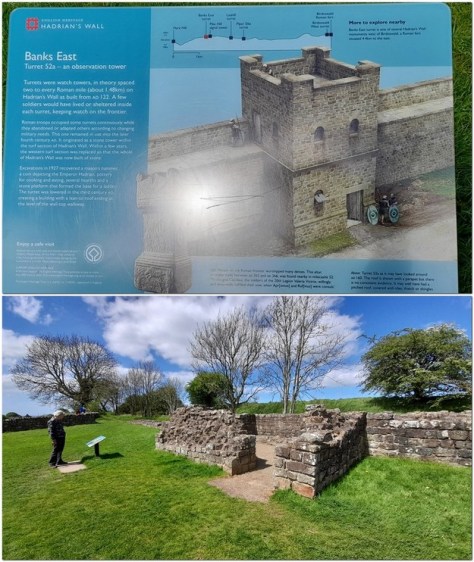

And we can also wonder about the lives of the men (and women) who were stationed along the Wall and where they came from. It’s not just the physical legacy of the Wall (and other settlements around the country) but also the genetic legacy that the Romans left behind, in their offspring from relationships with local women, legitimate or otherwise. Romans didn’t just come from Rome, but from all corners of the empire even from the easternmost provinces of the Middle East and beyond. The ‘Roman’ genetic signature has obviously been diluted by successive waves of invasion into these islands.

And we can also wonder about the lives of the men (and women) who were stationed along the Wall and where they came from. It’s not just the physical legacy of the Wall (and other settlements around the country) but also the genetic legacy that the Romans left behind, in their offspring from relationships with local women, legitimate or otherwise. Romans didn’t just come from Rome, but from all corners of the empire even from the easternmost provinces of the Middle East and beyond. The ‘Roman’ genetic signature has obviously been diluted by successive waves of invasion into these islands.

It was mid-afternoon, almost 15:30. I was sitting in the living room, reading one of Ann Cleeves’ Shetland series novels, and listening to Raising the Roof. My cellphone was on charge across the room, but I did hear the distinctive ping of a WhatsApp message but didn’t immediately bother to check it out.

It was mid-afternoon, almost 15:30. I was sitting in the living room, reading one of Ann Cleeves’ Shetland series novels, and listening to Raising the Roof. My cellphone was on charge across the room, but I did hear the distinctive ping of a WhatsApp message but didn’t immediately bother to check it out.

So who nearly brought about my demise?

So who nearly brought about my demise? years ago today (Friday 17 December 1971) I received my MSc degree in Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources from the University of Birmingham. Half a century!

years ago today (Friday 17 December 1971) I received my MSc degree in Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources from the University of Birmingham. Half a century!

One milestone for Brian and me was the publication, in 1986, of our introductory text on plant genetic resources, one of the first books in this field, and which sold out within 18 months. It’s still available as a digital print on demand publication from Cambridge University Press.

One milestone for Brian and me was the publication, in 1986, of our introductory text on plant genetic resources, one of the first books in this field, and which sold out within 18 months. It’s still available as a digital print on demand publication from Cambridge University Press.

I’ve often been asked how hard it was to resign from a tenured position at the university. Not very hard at all. Even though I was about to be promoted to Senior Lecturer. But the lure of resuming my career in the

I’ve often been asked how hard it was to resign from a tenured position at the university. Not very hard at all. Even though I was about to be promoted to Senior Lecturer. But the lure of resuming my career in the

Have you read—or even heard of—a novella called The Little Prince? No? Me neither.

Have you read—or even heard of—a novella called The Little Prince? No? Me neither.

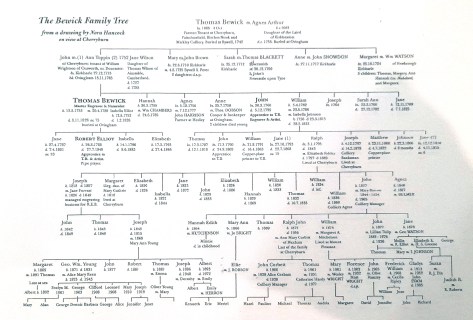

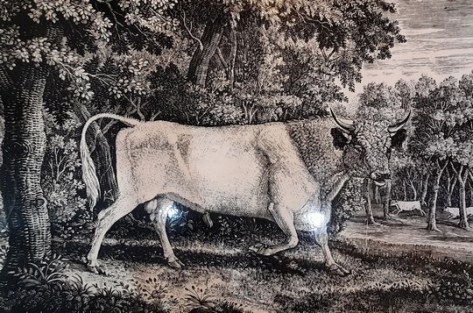

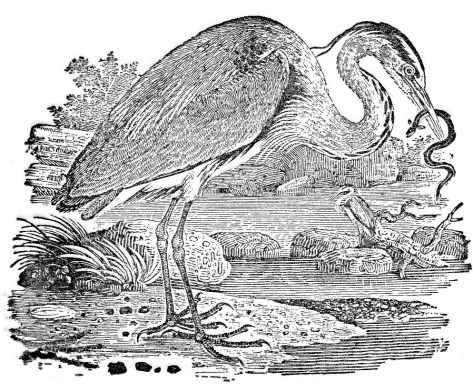

One of Northumberland’s most famous sons was artist and naturalist

One of Northumberland’s most famous sons was artist and naturalist

It was all about the

It was all about the

Among the species identified in the course of Jack’s dissertation research was Solanum ballsii from northern Argentina, which he dedicated to EK Balls in a formal description in 1944. However, in his 1963 revised taxonomy of the tuber-bearing Solanums (potatoes), Jack (with his Danish colleague Jens Peter Hjerting, 1917-2012) recognized Solanum ballsii simply as a subspecies of Solanum vernei, a species which has since provided many important sources of resistance to the potato cyst nematode.

Among the species identified in the course of Jack’s dissertation research was Solanum ballsii from northern Argentina, which he dedicated to EK Balls in a formal description in 1944. However, in his 1963 revised taxonomy of the tuber-bearing Solanums (potatoes), Jack (with his Danish colleague Jens Peter Hjerting, 1917-2012) recognized Solanum ballsii simply as a subspecies of Solanum vernei, a species which has since provided many important sources of resistance to the potato cyst nematode.